A lifelong journey of advocating for greater access to treatment for people with drug-resistant tuberculosis

24 March 2021

MDR-TB

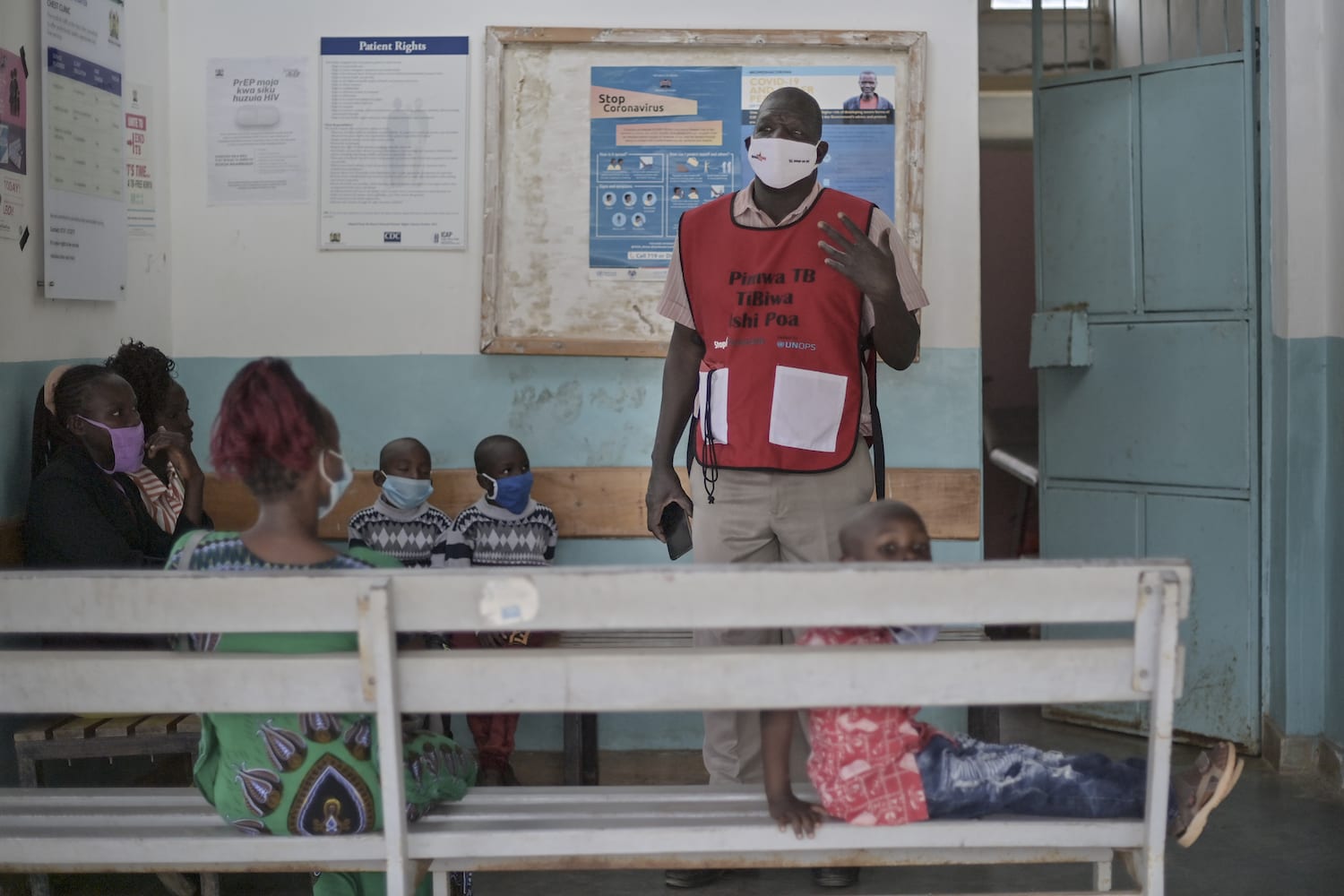

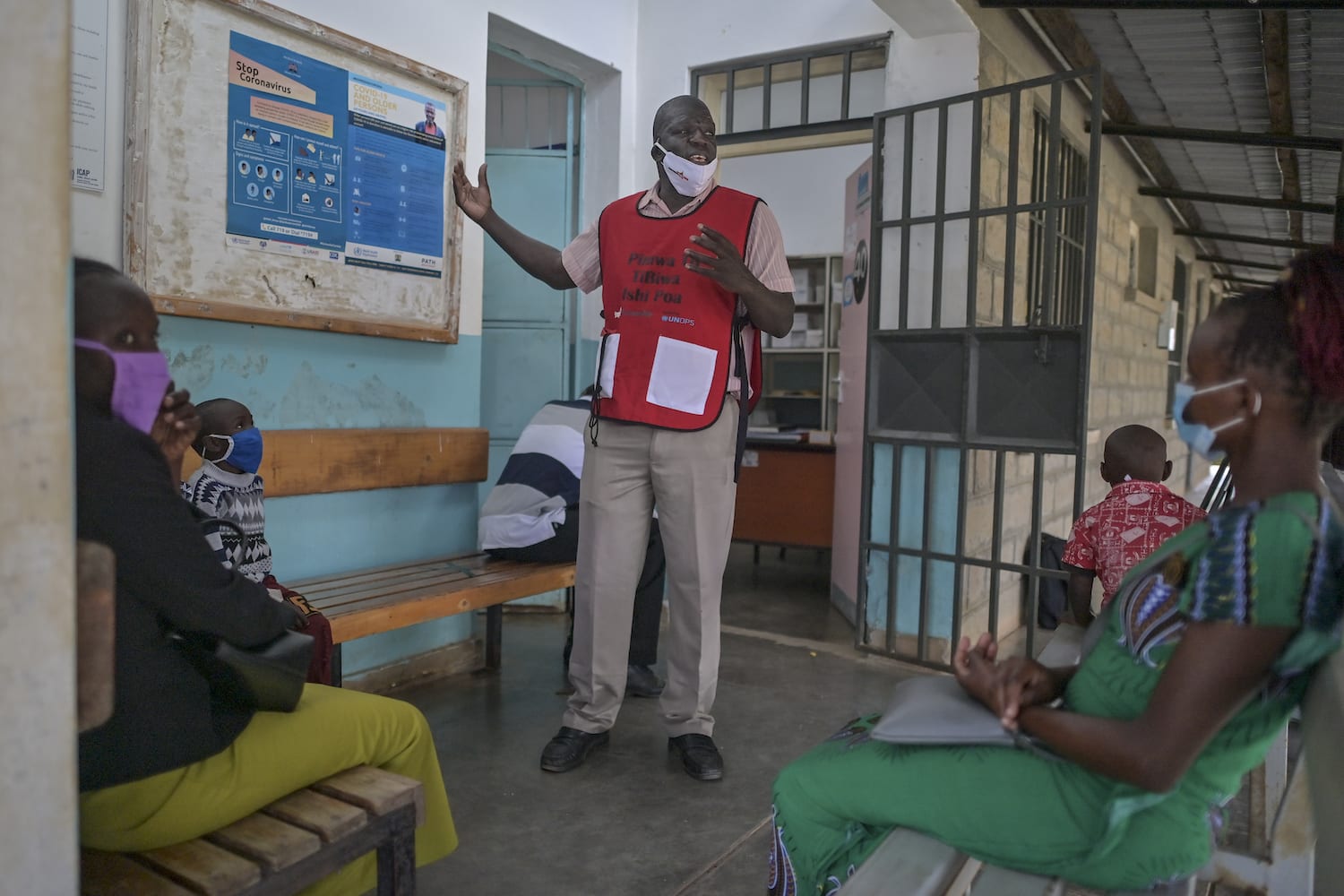

– By Peter Ngo’la Owiti, Executive director, Wote Youth Development Projects, Kenya

Peter Ngo’la Owiti is an advocate for tuberculosis (TB) patients in Kenya. Since 1994, he has lost 13 family members to TB, and his own son contracted TB (and was cured) at a young age. Peter now works as Executive Director of the Wote Youth Development Projects, a youth TB/HIV advocacy organisation based in Makueni County, Kenya. Peter is a tireless advocate for greater access to TB treatment and raising awareness of the disease in his community, and at national and international levels. Peter was recently appointed as representative of TB communities on the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) Facilitation Council. On the occasion of World TB Day, he gives us insights into the TB situation in Kenya.

One of our community members died, he had MDR-TB.

In my work, I care for those in my community who are affected by TB. Recently, Wilson (not his real name) was diagnosed with multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). Although, Kenya’s recent 2021 Integrated Guideline for Tuberculosis, Leprosy and Lung Disease (which follows a 2020 rapid communication) recommends phasing out injectables and moving towards all-oral bedaquiline (BDQ)-based MDR-TB or RR-TB (rifampicin-resistant TB)[1] treatment, injectable-based MDR/RR-TB treatment had been the norm for most patients previously. Under the previous policy, a patient diagnosed with MDR/RR-TB could receive an all-oral BDQ-based individualised treatment only if they met specific eligibility criteria. Treatment was prescribed on a case-by-case basis, and exclusively available on request from the central pharmacy. This individualised treatment approach often led to delays and poor health outcomes for MDR-TB patients. Unfortunately, Wilson, who was already very sick when he was diagnosed with MDR-TB, did not receive BDQ-based treatment in time – although he had been enrolled – and died from this curable disease. I believe that if the most effective treatment had been readily available irrespective of additional eligibility criteria, we could have prevented his death, and while I warmly welcome the recent change in the national guideline, it is still to be implemented widely.

Kenya, high burden country for TB, TB/HIV coinfection and MDR/RR-TB

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies Kenya as one of the 30 highest burden countries for TB (as well as among highest-burden countries for TB/HIV coinfection and MDR/RR-TB). In 2019, approximately 140,000 people fell ill with TB in Kenya, of which 84,000 (60%) were notified and treated. That same year, there were around 2,200 MDR/RR-TB incident cases in the country. An important driver of the TB epidemic remains HIV. Approximately 37,000 people living with HIV fell ill with TB in 2019. Yet, TB is a disease that can be prevented, diagnosed, treated and cured. Accordingly, everyone diagnosed with TB should be able to access care easily and be treated with the most effective medicines available, particularly for MDR/RR-TB, for which an all-oral treatment approach is now recommended by WHO.

Greater access to MDR/RR-TB treatment still needed.

When BDQ was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use as part of MDR-TB treatment in 2012, it was the first new medicine for TB in over 40 years. Supplies of BDQ to Kenya were initially donated by the originator pharmaceutical company Janssen (a Johnson and Johnson subsidiary), in partnership with USAID and through the Stop TB Partnership’s Global Drug Facility (as part of a programme that lasted between 2015 and 2019). In 2017, BDQ was added to the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, and in 2020, WHO recommended phasing out injectables in favour of all-oral, BDQ-based treatment for MDR/RR-TB, underlining the importance of this medicine – now the backbone for both short and long MDR/RR-TB treatment regimens – for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), in particular for countries with a high MDR/RR-TB burden like Kenya. With its role in enabling the switch from injectable-based to all-oral MDR/RR-TB treatment, BDQ now contributes to removing the need for painful injections and the harsh side effects from these older treatments, while also opening the way for home-based (and potentially self-administered) care.

Unfortunately, because of the high costs of some of the MDR/RR-TB medicines (including the cost of BDQ [2]), only a subset of patients in need have been treated. In Kenya, for example, despite the recent change in the national guideline, BDQ has mostly been used to treat XDR-TB (extensively drug-resistant TB) and other complex cases where injectable second-line TB medicines, such as kanamycin, cannot be used. However, kanamycin is an older injectable drug that WHO has recommended phasing out. If BDQ-based treatments had been more affordable, I believe that it should have been possible for many more patients with MDR/RR-TB to have been cured already, while avoiding the side effects of older injectable medicines. But it’s not too late and, with political will and more affordable treatment options, we can still catch up on MDR/RR-TB treatment numbers.

Greater investments needed to scale up TB treatments

The Global Fund provides 73% of all international financing for TB and has invested USD 7.2 billion in programmes to prevent and treat TB worldwide since its inception in 2002[3]. However, according to WHO, USD 3.3 billion per year are still needed to fill resource gaps for implementing existing TB interventions. While the price of BDQ has come down in recent years, the costs of treating MDR/RR-TB are still high and more is needed to address this major public health threat. Lessons from the HIV and hepatitis C responses, where access-oriented voluntary licensing enabled healthy generic competition and important price reductions for similarly innovative medicines – that are now well below 100 USD for a year of treatment or a 12-week cure, respectively – should also be applicable for MDR/RR-TB treatments (including BDQ).

Today, as we live through the COVID-19 pandemic, we fear that the gains made in TB may be lost. More than ever, we should consolidate those gains. To achieve this, BDQ, given its safety, efficacy and potential in simplifying MDR/RR-TB care, should be more widely available to all those in need, as per WHO’s recommendations, and now as per our national guideline. This guidance now has to be fully implemented within the country and we need to move away from case-by-case restricted MDR/RR-TB treatment approaches, and towards more streamlined public-health approaches in all high MDR-TB burden countries; this way others, unlike Wilson, will stand a chance of being cured of MDR/RR-TB.

[1] While RR-TB refers to TB that is resistant to rifampicin, MDR-TB is when the TB bacilli no longer responds to at least isoniazid and rifampicin, the two main first-line anti-TB drugs. WHO recommends all-oral BDQ-based treatment for both MDR- and RR-TB.

[2] The BDQ donation programme ended in March 2019.

[3] Global Fund data as of June 2020.

< >